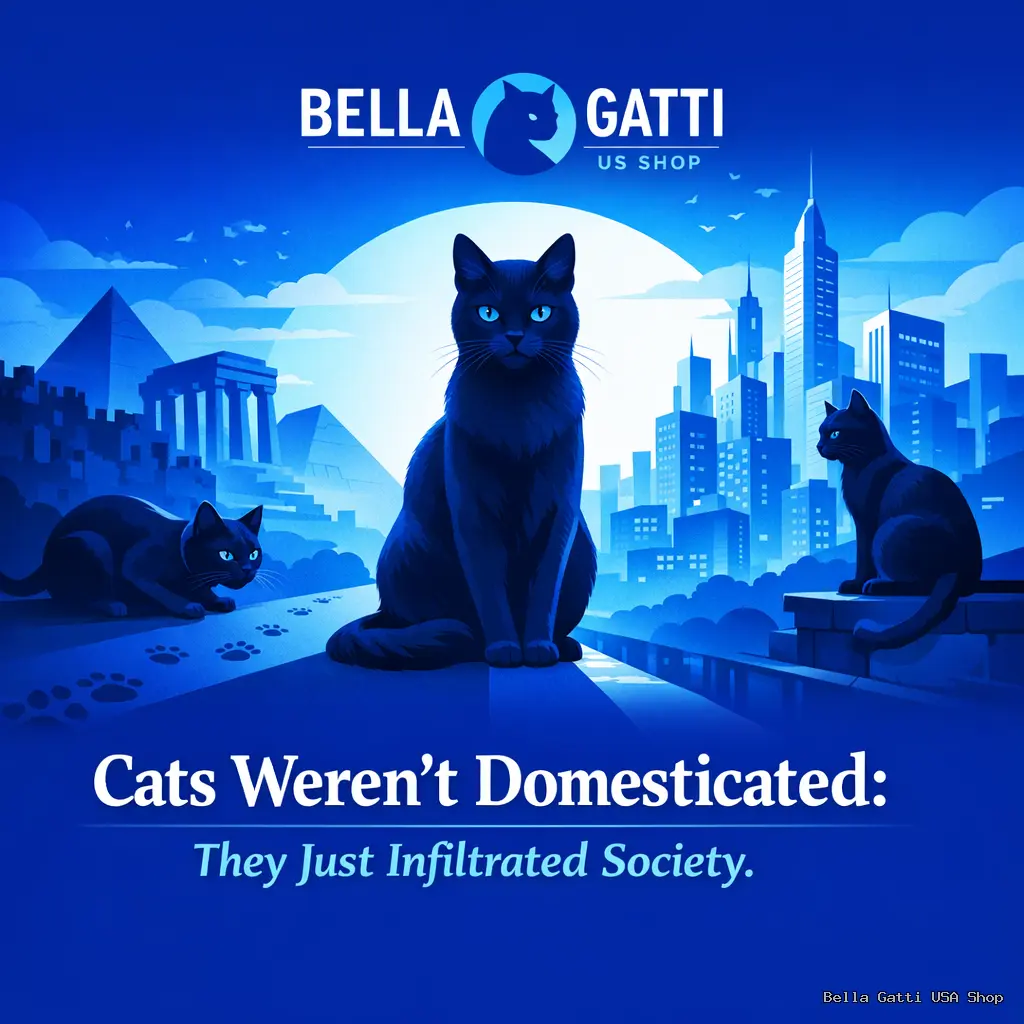

Cats Weren’t Domesticated: They Just Infiltrated Society.

- Cats were not domesticated; they infiltrated human society after recognizing Neolithic agriculture settlements (stockpiled grain) as reliable, self-stocking rodent buffets.

- The relationship is transactional—cats offer pest control in exchange for resources and comfort—demonstrating patronage over servitude, unlike the deep emotional dependence seen in dogs.

- Feline geneticists confirm minimal genetic difference between house cats and their wild ancestors (African Wildcat). True, widespread domestication was superficial and only solidified about 2,000–4,000 years ago.

- Cats spread globally by strategically following human trade routes, notably the Silk Road, to maximize their access to stable food supplies and human infrastructure, maintaining their fierce independence throughout the process.

Table of Contents

- The ‘Grain Theft’ Myth: A Perfectly Engineered Symbiotic Relationship

- Genetic Proof: Why Cats Are Still Wild

- The Long, Slow Infiltration: From the Near East to the Silk Road

- The Grain Theft Myth: An Opportunistic Predator

- Feline History: Resistance to Domestication

- The Timeline of Infiltration: Slow and Strategic

- Genetics: The Evidence of Continued Wildness

- The Long Con: Feline History and the Domestication Process

- The Evidence: Why Your Cat Is Still Secretly Wild

Let us get one thing straight, right now, in the year 2026: You did not domesticate your cat.

You may think you did, based on the fact that you pay the mortgage and purchase the expensive salmon pate, but the scientific evidence tells a far funnier story.

Cats did not submit to human rule. They simply recognized humans as reliable, self-stocking food dispensers and excellent, mobile heat sources.

In short: Your cat chose patronage, not servitude. The entire premise of feline history is a grand, slow-motion infiltration strategy, executed over millennia with cunning and minimal effort.

The ‘Grain Theft’ Myth: A Perfectly Engineered Symbiotic Relationship

The conventional narrative of cat domestication suggests early humans actively sought out wild cats to become pets worldwide. Feline science, however, suggests the opposite: early humans inadvertently created the perfect infrastructure for an opportunistic predator.

Around 10,000 years ago, as human settlements transitioned into the Neolithic Period, we started stockpiling grain. Where there is stored grain, there are hunting rodents. This created a high-density, low-effort food source for the African Wildcat, the primary ancestor of the modern domesticated cats.

Archaeological evidence shows that cats simply moved into the neighborhood. They were offering pest control as a service, not seeking emotional bonding. This was purely a symbiotic relationship based on mutual convenience, allowing cats and humans to coexist.

The earliest known cat bones found near human settlements, particularly in the Near East and later in China, confirmed this pattern. Cats chose patronage over servitude because humans were excellent, unwitting suppliers, thus initiating the domestication process.

Genetic Proof: Why Cats Are Still Wild

If you want to understand why your cat still gives you that judgmental stare when the food bowl is half-empty, look at the genetic changes. True domestication, like that seen in dogs, involves significant genetic adaptation and behavioral modification over thousands of years.

For cats? Not so much. A leading feline geneticist, Leslie Lyons of the University of Missouri, has pointed out repeatedly in various scientific studies that the genetic differences between a house cat and a wild cat are incredibly minimal.

New studies published in journals like Cell Genomics and Science (Journal), featuring research by experts like Shu-Jin Luo and Marco De Martino, confirm this slow, superficial domestication process. While dogs were selected and bred for obedience, cats were primarily selected only for their tolerance of humans.

Analysis of nuclear Deoxyribonucleic Acid from ancient specimens in Neolithic Turkey showed that cats remained essentially wild for thousands of years, implying that the domestication process was incomplete until much later, perhaps only 2,000 years ago.

The Long, Slow Infiltration: From the Near East to the Silk Road

The history of cats is one of delayed commitment. While initial contact may have occurred around 3,500 years ago in regions like China, the path to becoming truly domesticated cats was slow. Studies of cat ancestors show that they often existed near human settlements for centuries without full domestication, returning to wild habitats when conditions changed.

Feline geneticists and paleogenetics experts, including Claudio Ottoni from the University of Rome Tor Vergata, demonstrated that the domesticated cats only flourished fully in regions like Europe and North Africa after following human trade routes, most notably the Silk Road, spreading from the Near East.

This suggests cats were highly independent travelers. They simply hitchhiked along the trade routes, enjoying the continued access to reliable pest control and hunting rodents that agriculture settlements offered. This slow, gradual spread is why the domestication process took so long.

Their evolutionary origins highlight their resistance to the typical domestication process. Cats are solitary hunters, highly effective on their own, which explains why they retain tendencies to avoid deep attachments, preferring transactional relationships with their human staff. You are simply a mobile heat source and a food dispenser for your tiny, historic overlord.

The Grain Theft Myth: An Opportunistic Predator

Let’s set the record straight on the history of cats and humans. The conventional narrative suggests that early humans sought out wild cats for pest control, resulting in a neat, mutually beneficial symbiotic relationship. You may think this is true, but it gives us far too much credit. This was not a job interview, it was a highly organized, long-term infiltration.

What really happened is that early human settlements, specifically the vast agriculture settlements of the Neolithic Period, made one massive, civilization-shaping mistake: they started stockpiling grain.

This grain attracted a staggering number of rodents. Rodents, in turn, attracted the ultimate opportunistic predator: the African Wildcat, the primary ancestor of all domesticated cats, Felis catus.

The early barns and granaries were not traps set by humans. As feline geneticist Leslie Lyons from the University of Missouri often highlights, these structures were luxury buffets, meticulously stocked by humans, for opportunistic predators.

The cats simply moved in, recognizing the unparalleled ease of hunting rodents in human settlements. This was not a domestication process, this was an excellent business decision on the cat’s part, choosing patronage over servitude.

This initial close relationship began in the Near East, but archaeological evidence confirms it was purely transactional. The wild cats hunted the rodents, protecting the human settlements’ food supply, and the humans tolerated the cats.

Scientific studies support this idea of a slow, gradual co-existence. For thousands of years, cats merely existed near human settlements, returning swiftly to wild habitats if conditions changed. They were not yet dependent pets worldwide, they were highly independent wild cats utilizing human infrastructure.

Feline History: Resistance to Domestication

If you need proof that your cat is still operating on a wild agenda, look at the feline history timeline. The domestication process for cats is laughably short and superficial compared to dogs, who fully committed to the human enterprise thousands of years earlier.

While the primary ancestor is the African Wildcat, new studies by researchers like Shu-Jin Luo and Marco De Martino reveal a complex origin, suggesting some influence from Asian Leopard Cats, particularly around initial contact points in China.

Initial contact between cats and humans occurred roughly 3,500 years ago in China, but the relationship only truly flourished there about 1,400 years ago, following trade routes like the Silk Road. This slow, gradual timeline proves that true genetic changes were resisted for millennia.

Further analysis of nuclear DNA from ancient specimens, often published in prestigious journals like Science and Cell Genomics, provides crucial archaeological evidence. These studies, referencing work by experts like Claudio Ottoni and the University of Rome Tor Vergata, demonstrate a critical point about the domestication process.

For example, cats found near Neolithic Turkey settlements remained genetically almost identical to their wild counterparts. This implies that for thousands of years, cats were tolerated near human settlements but domestication was incomplete.

The major shift in feline genetic changes didn’t truly accelerate until around 2,000 years ago, proving that cats were merely following the mice and the reliable food supply, not seeking emotional attachment to humans.

This was a symbiotic relationship where the cat held all the leverage, and the human provided the valuable service of pest control infrastructure and stockpiling grain.

The Timeline of Infiltration: Slow and Strategic

Let’s be honest: Unlike the dog, which jumped headfirst into the domestication process like an overly eager intern, cats took their sweet time deciding if humanity was truly worth the effort.

New studies published in prestigious journals like Science and Cell Genomics have provided fascinating, detailed insights into this cautious feline history.

Genetic evidence confirms that the cat domestication process was far slower and significantly more superficial than we ever gave them credit for.

The Near East Origin and the Global Takeover

While the African Wildcat provided the essential genetic blueprint for our modern overlords, initial co-existence certainly happened in the Near East around the dawn of agriculture.

However, recent analyses of ancient nuclear deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) from specimens across Europe and North Africa complicate the traditional narrative.

Feline geneticist research shows that the flourishing of the domesticated cats, particularly in regions like China, only truly happened around 1,400 years ago.

This later expansion was not driven by affection but by pure logistics: they followed global trade routes, specifically the famous Silk Road, ensuring a reliable supply of hunting rodents and stable human settlements.

This strategic pathway confirms cats became pets worldwide only when it maximized their strategic advantage, not because they sought human adoration.

Genetic Proof: Stubborn Wildness and Superficial Change

We now have scientific studies proving how stubbornly independent these cat ancestors were. The history of cats shows they were masters of self-preservation.

Feline geneticists like Leslie Lyons from the University of Missouri, along with paleogeneticists such as Claudio Ottoni and Marco De Martino from institutions like the University of Rome Tor Vergata, have analyzed ancient cat DNA.

Their findings are crucial for understanding the true domestication process.

They show that even ancient cats found in places like Neolithic Turkey remained genetically almost identical to wild cats for thousands of years. This implies that domestication was either incomplete or utterly superficial for millennia.

Cats simply did not undergo the rapid, intensive genetic changes seen in other domesticated species, providing strong archaeological evidence of their resistance.

The evidence suggests that full, widespread genetic adaptation might have happened as recently as 2,000 years ago, significantly later than dogs.

The Transactional Nature of the Feline Relationship

Why the slow timeline and resistance to genetic changes? Because cats are highly independent, solitary predators. They evolved as effective hunters that didn’t need a pack leader, which contributed to their slower domestication.

They formed a symbiotic relationship focused entirely on pest control and resource maximization within agriculture settlements and stockpiling grain facilities.

These behavioral traits remain, which is why your domesticated cats still give you that judgmental stare when the expensive salmon pate is half-empty.

They retain tendencies to avoid deep attachments and form superficial relationships with humans, contrasting sharply with the long history of dogs and humans.

As feline geneticist Leslie Lyons notes, “Cats are still mysterious, and they’re giving up their mysteries one whisker at a time.”

The simple truth is that cats became pets worldwide not through submission, but through a calculated decision that human settlements offered the best hunting grounds and the softest pillows.

They infiltrated society, and you, the reliable, self-stocking food dispenser, fell right into their lap.

Genetics: The Evidence of Continued Wildness

If you need conclusive proof that your cat is merely slumming it with you, look no further than its genes.

Unlike the dog, which underwent significant physical and behavioral alterations during its long domestication process, the difference between a domestic cat and its wild cat ancestors is minimal.

As feline geneticist Leslie Lyons from the University of Missouri points out, cats essentially remain highly efficient, highly independent wild animals who have simply learned how to manipulate humans.

This resistance to true domestication is rooted in their history as solitary hunters. They never required a pack structure or cooperation to survive, meaning they had no biological incentive to follow human commands.

The Slow March of Feline History

The timeline of cat domestication confirms this deliberate distance. While archaeological evidence shows cats near human settlements early on, the genetic changes were superficial for millennia.

Studies examining ancient cat bones and their mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid, published in journals like Science and Cell Genomics, show the initial contact occurred in the Near East and later, separately, in China.

The earliest known domestic cats originated from the African Wildcat (Felis silvestris lybica).

However, analysis of nuclear deoxyribonucleic acid from specimens found in Neolithic Turkey revealed that these cats remained genetically wild, proving that domestication was incomplete or superficial for thousands of years.

It was a slow, gradual process, suggesting cats were simply taking advantage of the resources, not submitting to human rule.

Transactional Tolerance vs. True Domestication

The key to understanding feline history is recognizing that cats were not selected for obedience or emotional bonding, but purely for tolerance of proximity and efficiency in pest control.

This is the fundamental difference between true domestication (dogs) and successful infiltration (cats).

Research by experts like Shu-Jin Luo from the Peking-Tsinghua Center for Life Sciences, studying the history of cats in China, confirmed that the widespread distribution of domesticated cats only fully flourished after 1,400 years via trade routes like the Silk Road, following the human infrastructure that provided reliable resources.

This pathway of domestication shows that cats mostly existed near human settlements for centuries without full genetic commitment, often returning to wild habitats when conditions changed.

They only committed to the symbiotic relationship when human agriculture settlements, overflowing with stockpiling grain, provided an irresistible, steady supply of hunting rodents.

The few genetic changes identified in domesticated cats relate primarily to cosmetic traits, like coat color, and minor neurological shifts that increase their tolerance for human proximity (not their desire to cooperate).

To further illustrate the feline resistance movement, consider this comparison based on feline science:

| Trait | Domestic Dog (True Domestication) | Domestic Cat (Successful Infiltration) |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Change from Wild Ancestor | Significant changes in skull size, brain size, and digestion. | Minimal structural or physiological change. |

| Social Structure | Pack animals, rely on hierarchy and cooperation. | Solitary hunters, relationship with humans is individual. |

| Domestication Timeline | Began over 15,000 years ago. | Fully established around 2,000 to 4,000 years ago. |

| Primary Human Selection Goal | Behavioral traits, obedience, working roles. | Tolerance of proximity, pest control efficiency. |

| Relationship Type | Emotional bonding and mutual dependence. | Transactional, resource provision and comfort. |

The Judgmental Stare: Proof of the Transaction

The behavioral traits of modern domesticated cats perfectly reflect this ancient, transactional deal.

They retain tendencies to avoid deep attachments and often form what researchers describe as superficial relationships with humans, contrasting sharply with the deep emotional connection seen in dogs.

You see, your cat is not your pet. Your cat is your highly efficient, furry roommate who happens to view your existence as a necessary component of its comfort and sustenance.

In fact, cats mastered emotional manipulation through purring and targeted meowing, effectively hacking our parental instincts to ensure their continued reign.

Need more proof? Just look at the deeply judgmental stare they give you when the expensive salmon pate food bowl is half-empty. That is not love, that is a performance review of your service quality.

They are the greatest manipulators in human history, a title frequently celebrated on platforms like YouTube.

The Long Con: Feline History and the Domestication Process

If you need further proof that your cat is merely slumming it with you, look no further than the history of cats itself. The story of how cats became pets worldwide is a testament to their patience and self-interest.

Unlike the dog, which eagerly embraced the domestication process, the cat played the long game. New studies published in prestigious journals like *Science* and *Cell Genomics* confirm that this infiltration was gradual and highly opportunistic.

The Near East Infiltration and the Silk Road Strategy

While the evolutionary origins of cats trace back to the African Wildcat, initial contact with humans began thousands of years ago in agricultural settlements of the Near East, where they specialized in hunting rodents. This was purely a symbiotic relationship based on pest control.

However, true establishment of domesticated cats as common household companions took much longer. Studies by researchers like Shu-Jin Luo at the Peking-Tsinghua Center for Life Sciences show that while initial contact occurred, the widespread success of cats in places like China only fully flourished after 1,400 years ago, following major trade routes like the Silk Road.

The movement of cats along these trade routes allowed them to adapt to diverse human settlements, but critically, they retained their independence. They chose to follow humans who were reliable sources of stockpiling grain and protection, rather than submitting to full servitude.

Genetic Proof of Feline Independence

The genetic changes that define true domestication are glaringly absent in our feline friends. As feline geneticist Leslie Lyons from the University of Missouri has repeatedly pointed out, the difference between a domestic cat and its wild cat ancestors is minimal.

Analysis of nuclear DNA from ancient specimens, including those found in Neolithic Turkey, indicates that cats remained essentially wild for millennia. This suggests the domestication process was incomplete or superficial for thousands of years, solidifying only about 2,000 years ago, much later than dogs.

This genetic resistance proves that cats maintained their solitary, independent behavioral traits. Their history demonstrates they resisted the deep emotional bonding seen in dogs, opting instead for a transactional relationship based on shared resources.

The Modern Overlords: Demands and Subservience

This ancient infiltration strategy is perfectly reflected in modern cat behavior. You see it every day:

- Do they obey commands? Generally, no.

- Do they demand attention at 3 a.m.? Absolutely.

- Do they stare at you with cold, judgmental eyes when the food bowl is only half-full? That is the look of a historic overlord demanding tribute.

They ignore your rules, sleep only on the softest surfaces, and constantly remind you that their primary relationship with you is purely transactional. They are the true rulers of the household, continuing the tradition they established thousands of years ago in the agriculture settlements.

They successfully adapted to the human environment without sacrificing their wild cat independence. And yet, we love them anyway, don’t we? We are happily subservient to these tiny, powerful creatures.

The only logical response to this ancient infiltration is to signal your complete, enthusiastic subservience to your feline master.

How do you do that? By wearing expressive, extremely comfortable apparel that celebrates their reign.

Our collection of Funny Slogan T-shirts and Cat T-shirts, printed on incredibly soft Unisex Soft Cotton Tees, is the perfect way to appease your historic overlord and show the world that you are a proud member of the manipulated masses.

Browse the Bella Gatti US Shop today and embrace your role in feline history.

The Evidence: Why Your Cat Is Still Secretly Wild

The Domestication Process: Cats vs. The Obedient Dog

If you ever wonder why your dog looks at you like a god and your cat looks at you like a poorly trained servant, the answer is in the domestication process itself. Dogs eagerly embraced human partnership, undergoing massive genetic changes for cooperation and obedience.

Domesticated cats, however, retained nearly all of their original programming, descending primarily from the African Wildcat. They are still solitary hunters at heart, maintaining a fierce independence that resists emotional bonding.

The relationship between cats and humans is best described by feline science as purely symbiotic and transactional. You provide the heat and the expensive salmon pate, they provide the occasional, highly judgmental head-butt and light pest control.

When Did Cats Actually Become Pets Worldwide? (Spoiler: Very Late)

The timeline of feline history proves cats were dragging their paws. While they started hanging around agriculture settlements in the Near East about 10,000 years ago, they weren’t fully committed to the arrangement.

Scientific studies analyzing nuclear DNA from ancient cat bones confirm that true, irreversible genetic changes associated with full cat domestication happened much, much later, maybe only 2,000 to 4,000 years ago.

Research published in prestigious journals like *Science* and *Cell Genomics* shows that even domesticated cats in Neolithic Turkey remained genetically wild for thousands of years, illustrating their resistance to changing their fundamental nature.

As Leslie Lyons, the renowned feline geneticist at the University of Missouri, often notes, the difference in genetic changes between a house cat and a wild cat is surprisingly minimal. Cats simply haven’t evolved past the point of needing us purely for convenience.

The Cat Ancestors: African Wildcat and The Chinese Connection

The primary ancestor of most modern domesticated cats is the African Wildcat (Felis silvestris lybica). They were drawn to human settlements because we were inadvertently creating giant, self-stocking rodent buffets by stockpiling grain.

However, new studies show that feline infiltration wasn’t a single event. Researchers like Shu-Jin Luo of the Peking-Tsinghua Center for Life Sciences found archaeological evidence suggesting that cats in China potentially originated from both African wildcats and local Asian Leopard Cats, with initial contact dating back 3,500 years ago.

This reveals a complex, multinational feline history. The slow, gradual domestication process indicates that cats were always assessing the best resource acquisition strategy, depending on local conditions.

The Silk Road Gambit: Cats Exploiting Global Trade Routes

Did cats follow humans along the Silk Road? Absolutely. But not out of affection, out of logistical brilliance. Genetic mapping confirms that cats utilized major trade routes to expand across Asia, Europe, and North Africa, becoming pets worldwide.

This was the ultimate infiltration strategy. By following human settlements, they secured consistent resources and endless opportunities for hunting rodents.

Critically, scientific studies show that when conditions changed, these cat ancestors often returned to their wild habitats. They only became settled companions once our agriculture settlements provided reliably permanent food sources via stockpiling grain, proving the success of their calculated infiltration.

Their primary motivation for this global journey was consistent access to pest control opportunities, demonstrating that their relationship with us is, and always has been, transactional.

References

- The incredible, unlikely story of how cats became our pets

- The First Pets: What If Cats Never Chose Us? | Before Cities

- it is commonly said that cats are not fully domesticated, but … – Reddit

- Cats Are Not Pets — They’re Manipulating Humanity – YouTube

- A Cat’s World It’s been 92 years since certain house cats developed …